Johann Sebastian Bach’s ambitious oratorio, St. Matthew Passion, is considered to be one of the greatest masterpieces of sacred music of all time. The work sets the story of Jesus’s trial and crucifixion to music utilizing three source texts – Matthew chapters 26 and 27 from the Bible, German chorales that Bach’s congregation would have known, and a poetic theological commentary by a librettist who went by the name Picander (and whose real name was Christian Friedrich Henrici). Bach’s St. Matthew Passion includes nine scenes: an introduction, Jesus’ anointing in Bethany, the Last Supper, Jesus praying in the garden of Gethsemane, Judas’ betrayal, the trial before Pontius Pilate, Judas in the temple, the crucifixion, and finally Jesus’ death on the cross and burial.

The Passion is a massive piece, and it features a double orchestra and a double chorus. Each orchestra includes violina, violas, a viola da gamba, two flutes, two oboes, organ, and a bass section consisting of cello, double bass, and bassoon. In addition to the double chorus, there are also groups of soloists which includes the Evangelist – a tenor who sings a majority of the Biblical text, mostly in a recitative accompanied by the organ and a bass instrument – and Jesus, who is sung by a bass or baritone soloist. Together, the vocalists and instrumentalists perform powerful choruses, traditional chorales, recitatives, and elaborate arias over the course of two and a half hours (with a break between the two parts) – clocking in at the longest piece Bach ever wrote.

St. Matthew Passion was first performed on April 11, 1727 (Good Friday) at St. Thomas Church in Leipzig, where Bach was working as cantor. In addition to the premiere of the Passion, a sermon would have also been preached between the two halves, numerous hymns and motets would have been sung by the congregation, and there were likely additional readings, making for a quite lengthy service. In 1736, Bach revisited St. Matthew Passion and made several significant revisions that comprise the surviving work we have today, including giving a full bass section to each orchestra (they initially shared the continuo) and changing the ending of the first part.

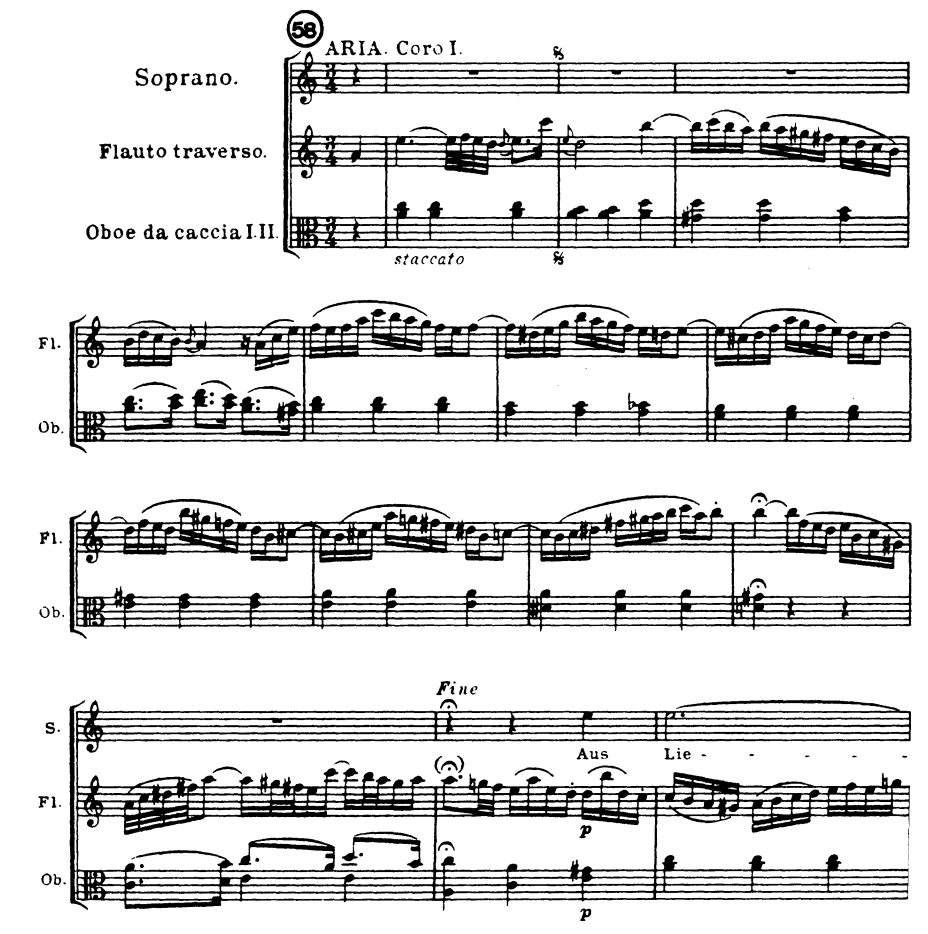

The primary flute excerpt from St. Matthew Passion comes from no. 58, “Aus Liebe will mein Heiland sterben.” At this point in the Passion, Jesus has been arrested and is standing before Pontious Pilate. Pilate asks the crowd whether he should release Jesus or the notorious prisoner, Barrabas. When the crowd calls for Barrabas’s release and Jesus’s crucifixion, Pilate asks “But what evil has he [Jesus] done?,” and a soprano soloist offers no. 58 as a reply. The translated text is as follows:

Out of love is my Savior willing to die,

Though of any sin he knows nothing,

So that eternal damnation

And the sentence of judgment

May not rest upon my soul.

In addition to the translation for no. 58, I highly recommend familiarizing yourself with both Matthew 26 and 27, as well as having a text and translation for the Passion nearby (this translation available on Emmanuel Music here is great). If you’ve been following along in this orchestral excerpts blog series, you’ll know I’m a big believer in familiarizing yourself with the context – context matters!

Performance Considerations

The flute’s pickup note begins “Aus Liebe will mein Heiland sterben,” and it is quickly joined by a pair of oboes marking time. The soprano doesn’t join until beat three of the measure with the fermata, where Bach marks the flute’s line piano.

The absence of a bass instrument/voice throughout this aria combined with the instrumentation (the flute, oboe, and soprano all play and sing in the same range) gives it a hauntingly empty feeling. Similar to the accusations against Jesus, this aria evokes loneliness, and is foundationless and bereft. Use and embrace the lack of a bass voice and choose your color carefully to help communicate the text.

There are several other elements that will help you to achieve this as well. The first is to keep a steady tempo (it is usually around 50-58) without allowing the breath to interfere. There are plenty of places to breathe within this excerpt, but ensure every breath supports a full line. In addition, be careful not to over-romanticize the music with rubato or vibrato – keep in mind that in the Baroque era, vibrato was used as an ornament (so be very selective about where you use it), and strive for clarity in the rhythm.

Secondly, though Bach didn’t write a ton of dynamics in the excerpt, it is an excellent example of deriving dynamics by following the contour, or the shape of the musical line. When the notes go up, crescendo – when they go down, diminuendo. That said, don’t let high notes cause sudden changes in dynamics. For example, in the first full measure of the excerpt, be careful not to let the high C be louder than the notes before or after it, but rather relative in dynamic to them.

Finally, emphasize dissonant harmonies and maintain the energy through held notes, and especially through the end of the notes with fermatas. Don’t let the pitch fall flat, and hold off a diminuendo until the very last second (think of the very end of a bell dinging).

There’s not much more to it – conveying the emotion behind the text is key to this moving excerpt from Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. As you work on it, let me know what other tips and tricks helped you in the comments below!