I figured it would be fun to have the fourth installment in the orchestral excerpts series be the solo from the fourth movement of Johannes Brahms’ fourth symphony! Like the other three blogs on orchestral excerpts, this one will start out with background information and the context of the solo.

Though Brahms wrote his fourth and final symphony in 1884 and 1885, the origins of the fourth movement stem all the way back to the early 1700s.

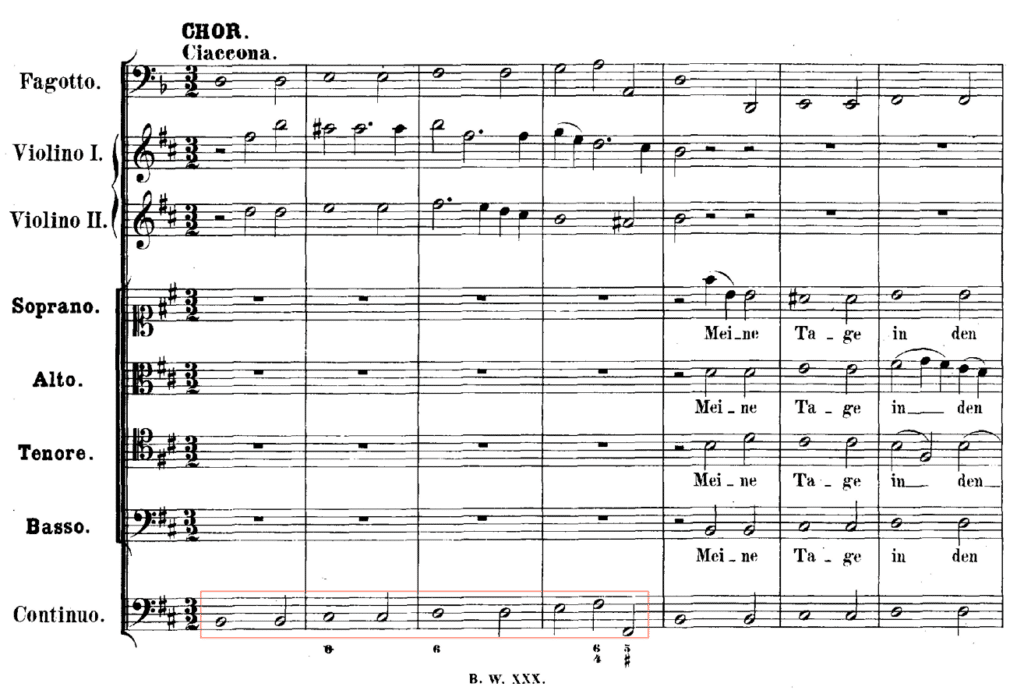

Likely between 1707-1710 in Arnstadt, Germany, Johann Sebastian Bach wrote a seven-movement Cantata (no. 50) called Nach dir, Herr, verlanget mich (For Thee, O Lord, I long, BWV 150) for two violins, bassoon, basso continuo, and of course, choir.

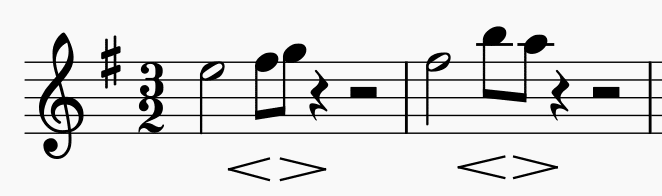

The final movement takes the form of a chaconne, which is a short theme or harmonic progression heard in the bass line that is continually varied. Below you can see the chaconne’s four-bar theme in the bass of the Cantata:

Now that you’re familiar with Bach’s chaconne, fast forward to 1882. Brahms played it for a friend and asked “What would you think of a symphony written on this theme some time? But it is too clumsy, too straightforward. One must alter it chromatically in some way.”1

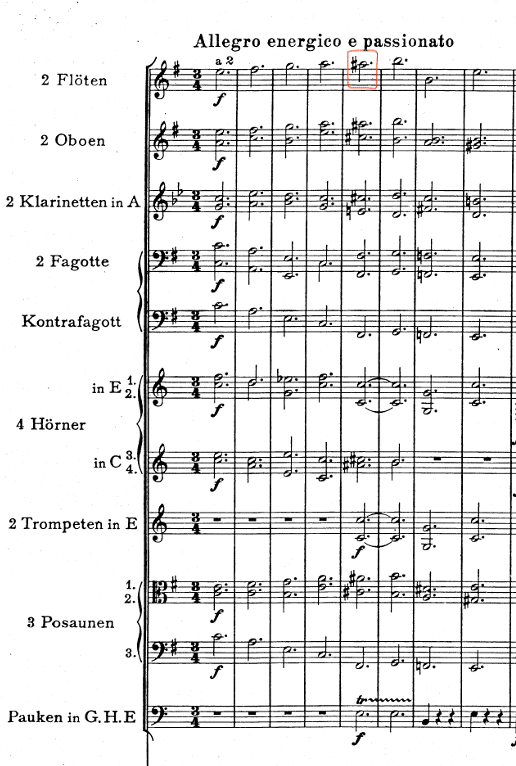

Two years later when he was writing the symphony, Brahms made such changes by adding a chromatic note between the last two pitches. He also changed the key of the theme from b minor to e minor, as well as the meter, therefore stretching out the previously four-bar chaconne to eight bars.

After this theme is presented, it is then variated upon thirty times, followed by a coda. Another difference between Bach’s chaconne and Brahms’ is that Brahms’ is considered to be a passacaglia. While the terms “chaconne” and “passacaglia” are often used interchangeably since they’re both variations on a short repeated theme/harmonic progression, they are slightly different. In a chaconne, the theme and its variations stay in the bass line. In a passacaglia, the theme and its variations can be heard in any line.

As the “theme” is quite simple, Brahms was also able to be enormously flexible throughout his variations. For example, the harmonic structure is sometimes adapted (i.e., he often prepares the dominant in different ways), he modulates to other keys, and adjusts tempi.

The fourth symphony premiered on October 25, 1885 in the small town of Meiningen, Germany, with Brahms himself conducting.

Performance Considerations

The flute’s variation on the theme is super expressive and intense. One of the best ways to capture the emotion in this solo is to carefully plan where you’ll incorporate vibrato. But before we jump into tips for how to do that, I want to mention a couple of other quick things.

The intensity and expression of this excerpt can also be demonstrated by milking the rhythm. Rhythmic accuracy is, of course, super important (as is counting the rests accurately – don’t skip any rests in this excerpt), but see how much you can stretch the rhythm while keeping it in time.

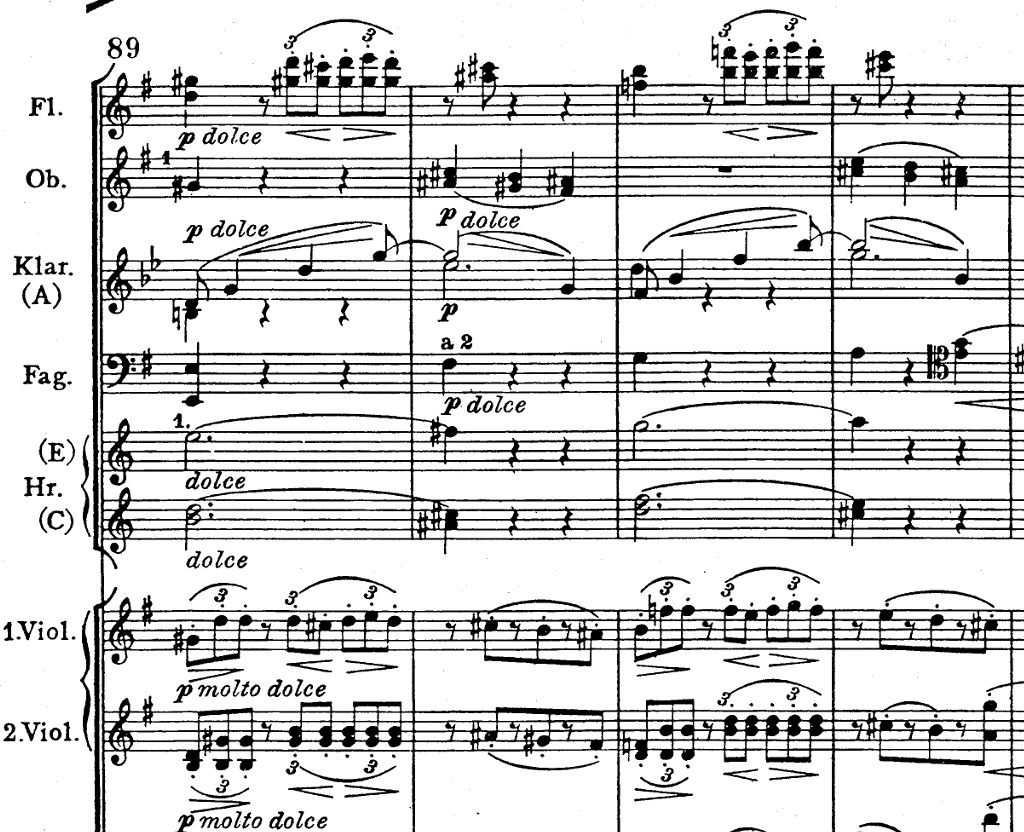

Like other excerpts, it is important to communicate to the jury that you understand the context and structure of this solo (and the piece). Think of it in three distinct sections; bars 89 through 92, bars 93 through 96, and then the actual solo (bars 97 through 105).

Section 1: Bars 89-92

The flute plays with the violins in this section, so be careful to match your articulation to theirs. It should be light and delicate (it’s marked molto dolce in the violin part).

In my opinion, the triplets actually aren’t as tricky as the eighth notes in 90 and 92. Flutists often play those eighth notes as if they’re on their own. However, if you study the violin part, you can see that the note is technically the first of three that lead into the next measure.

Let the panel know that you know the violin part by playing those eighth notes (and the quarter in 91) with the same delicacy and lightness as the triplets, at the same dynamics the violins would play it, and with motion and direction.

Section 2: Bars 93-96

Two flutes and two clarinets play the downbeats in the next section and the violins and violas play on the offbeats. It should be super legato (practice very slowly to make sure your fingers are all moving at the same time and each note is given the correct amount of air) and with a gentle tone.

Keep in mind the clarinet does not use vibrato – while this doesn’t mean you can’t use any vibrato, it should be minimal to match the clarinet, and the places you use it should be very intentional.

Lastly, make sure you don’t slow down during this section – the diminuendo is not accompanied by a ritardando!

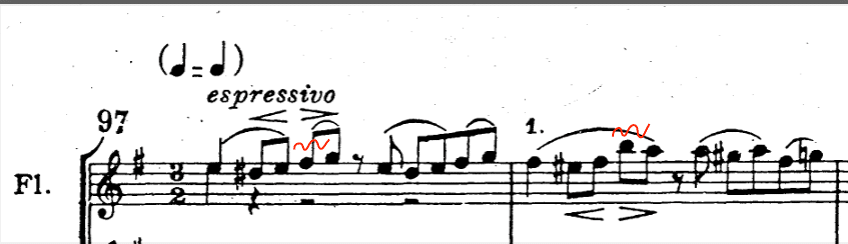

Section 3: Bars 97-105

This is where all the information about the passacaglia mentioned above comes in handy. To show the judges you understand the movement, I recommend asking a friend to play the passacaglia line while you play the solo (or record yourself playing the passacaglia and then play the solo over it). This will give you a better understanding of the structure of the solo (and therefore able to make that structure clear while you are playing), allow you to hear the continuation of the line, and show you where the height of the tension is.

This section should be very warm – stretch it as much as you can, sing through it, and be extremely expressive! Note that Brahms wrote “expressive” in the score and not piano – the piano comes from the accompanying instruments (which play when the flute rests – hence why the rhythm is super important). The flute solo itself is not necessarily piano, though, which is a good thing because it allows for more freedom in dynamics.

Earlier in the blog, I mentioned we would discuss vibrato – this is where it becomes super important.

There are a total of 26 appoggiaturas in this solo – make sure to lean slightly on each one. However, the ones on the second big beats are the most important, and those are the notes that should get that shimmer of vibrato. Many of these have hairpins underneath – make sure to emphasize them!

Flutist Emily Beynon suggests a great way to work on both the vibrato on the second big beat and the hairpins underneath. The first step she recommends is to turn the first beat into a half note and practice growing through it until you reach the second big beat, at which point you’ll play it as written and decrescendo.2

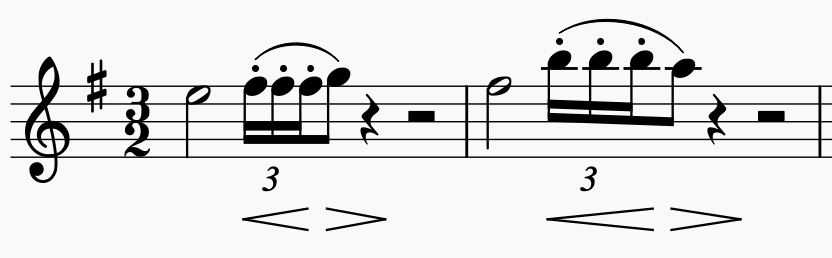

To get the vibrato to shimmer on the second big beat, she recommends the following exercise:

Once you are comfortable with three notes on the first eighth note of big beat two, reduce the number of rearticulated notes to two:

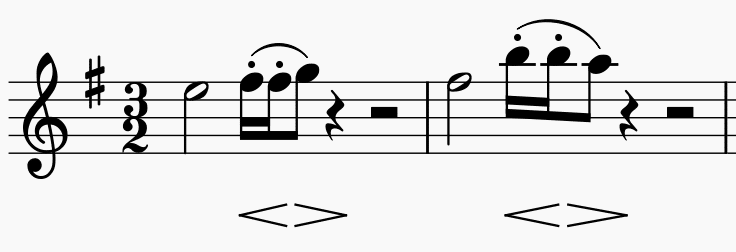

Finally, play as written and recreate the same feeling with your vibrato.

As I mentioned earlier, be very intentional with how and where you use vibrato in this excerpt as including lots of it communicates a lack of understanding about the structure and what else is going on in the orchestra as you play.

The end of the solo lands on an E major (!) chord – think “bright” on that last note!

What other tips and tricks do you use while working on the excerpt from Brahms’ fourth symphony? I’d love to hear them in the comments!!

(1) Quoted in Walter Frisch, Brahms: The Four Symphonies (New York: Schirmer Books, 1996), 131.

(2) Emily Beynon, “Brahms 4: Orchestral Flute Tutorial,” Youtube Video, 11:04, May 7, 2020, https://youtu.be/iw_ZYOgx24Q.