One of our most popular excerpts is the Scherzo from Felix Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It is commonly featured on audition lists because it showcases a flutist’s breath control, understanding of phrasing, and ability to tongue cleanly, lightly, and with a clear tone.

If you’ve read the last two blogs on orchestral excerpts, you know context matters as it leads you to make better decisions regarding dynamics, articulation, affect, and much more. As such, here is the background information and context of A Midsummer Nights Dream, followed by performance considerations and tips!

A Midsummer Night’s Dream is a comedy by Shakespeare written around 1595-1596. There are multiple simultaneous and weaving plot lines that are (in my opinion) a bit hard to follow over the course of the play’s five acts.

Essentially, the play tells three stories that all come together by the end:

- A wedding between Theseus, Duke of Athens, and Hippolyta, Queen of the Amazons

- A love square (yes, a square – not a triangle) – there are two young couples who fall in and out of love with each other

- An argument between Oberon, King of the Fairies, and his wife, Titania, Queen of the Fairies

As the story continues, Oberon, King of the Fairies, has his malicious servant Puck (a.k.a. Robin Goodfellow) gather a magic flower. When the juice from the magic flower is placed on the victim’s eyes while they’re sleeping, it makes them fall in love with the first thing they see when they wake up. Puck puts this magic flower juice on Titania, which is how Oberon seeks revenge due to their argument. However, Puck also puts it on one of the guys wandering in the woods, hence causing the chaos between the two couples and the love square.

By the end of the play, everything is resolved. The four people in the woods pair off as couples, the argument between Oberon and Titania is resolved, and the Duke of Athens and Queen of the Amazons get married.

Mendelssohn’s Incidental Music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Mendelssohn wrote the overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream in July/August of 1826 at 17 years old. It was privately premiered at the Mendelssohn residence and publicly premiered in February of 1827.

In 1843 (16 years later), Mendelssohn was invited by the drama-loving King of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm IV, to compose incidental music (background/accompanying music for a play). What resulted was not only the 12 movements and finale to A Midsummer Night’s Dream, but also incidental music for Jean Racine’s Athalie, and Sophocles’ Oedipus.

Included among the 12 movements and finale are the famous Scherzo (the selection where our excerpt appears), Nocturne, and Wedding March. Mendelssohn strategically used motives and material from the overture to construct the new music for the rest of the play, rather than composing an entirely new set of pieces. The work in its entirety was premiered with the play on October 14, 1843.

The Scherzo functions as an intermezzo between the first and second Acts and sets the scene of Act Two. This is when the audience is first introduced to the fairies.

Performance Considerations

There are so many things to keep in mind while working on the excerpt from the Scherzo! One of the biggest pieces of advice I can offer is to remember this is more than an excerpt – it’s a piece of music meant to accompany a story. It’s super easy to get lost in the technique of this excerpt and lose the character and shape. Remember, you’re introducing the fairies – you need to play lightly (as cheesy as it sounds, imagine fairies flying around), with a clear tone, and cleanly.

The best way to start learning this excerpt is to play everything slow and slurred. This helps to ensure your fingers can get all of the right notes and are even, your air is steady throughout, and each note has a good tone quality. As you work on this excerpt, also keep in mind that maintaining a steady tempo is of utmost importance (it is usually played between 82-90 bpm). Therefore, before you add in the tonguing, practice it slowly and increasing the metronome while playing everything slurred. Also try setting the metronome to click on the second or third beats – this will really challenge your ability to stay exactly on beat!

Once you have the excerpt down with the metronome slurred, it’s time to start working on the double tonguing! Again, slow practice is the key. In my experience, different syllables sometimes work better in different registers of the flute – experiment to see what works for you! I know a lot of people prefer “tah (or tee)/kah,” but also experiment with “duh/guh” to see which syllable produces the cleanest sound in each register. This excerpt requires a more legato double tongue, which for me personally is best produced by using “duh/guh.”

Practice the excerpt slowly using the syllables you have chosen. Here are a couple exercises to help you practice the double tonguing.

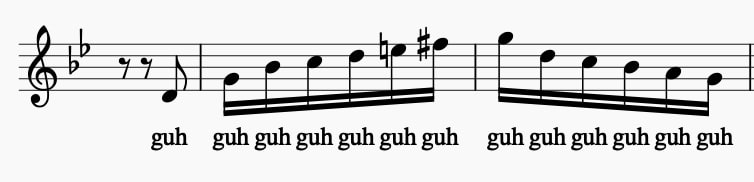

- Practice the entire thing on the second syllable (“guh guh guh” or “kah kah kah”) to help isolate and strengthen it:

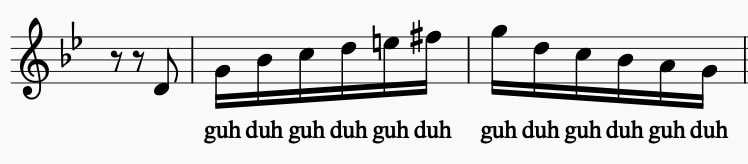

- Switch the order of the tongue (start on the back syllable – “guh duh” instead “duh guh.” When practicing this exercise fast, I like to think “goodie goodie goodie” as it rolls off of my tongue a bit easier than “guh duh!”):

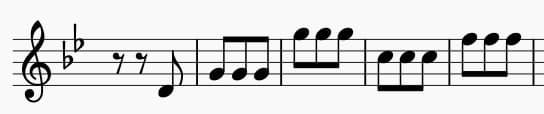

- Use alternate rhythms in conjunction with the double tonguing:

- Play each note twice:

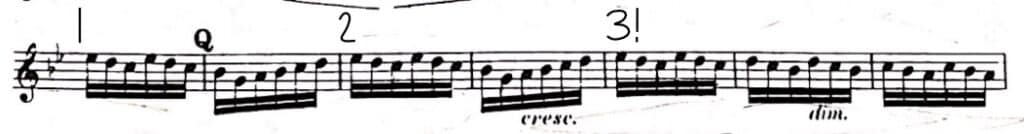

Breathing is also one of the trickiest parts of this excerpt. Traditionally, it has been expected that flutists play from the pickup to one before P all the way to the two bars of rest after Q in only three breaths. The first breath is after the eighth note G, nine bars after P. The second is after the eighth note G four before Q, and of course the third is at the two bars of rest near the end. If you have to take an emergency breath, take it in the third bar of Q and omit the G.

There are a handful of tips and tricks to help you practice breathing and work towards only taking the three breaths in this excerpt. Don’t forget to give yourself grace – learning to take deep breaths and working up to a greater lung capacity takes time (months!), so please be patient with yourself!

I like to use the analogy of putting gas in a car for the breathing in this excerpt. When I fill up a tank of gas, even after it is full, I like to shake the pump to drop the last bits of gas into the tank. I do the same for this excerpt with my air. I take a slow, deep breath (through the nose is best, as it helps the breath go deeper!), then a second breath to “top it off,” and then a third breath – make sure to get all the gas drippings in the tank! Also, ensure you don’t accidentally let any air slip out when you’re topping the breath off.

Fill up your tank, and then practice the excerpt at a piano dynamic, only playing the first note of each bar. Taking away the fingering is a great help you isolate the breathing!

When you’re able to make the breaths using that exercise, try bumping the dynamic up to a mezzo piano. Then perhaps try adding some more notes such as this (sticking to a single note in each bar eliminates the need to change the air direction and aim for different notes – again, this is intended to help you isolate the breath):

I would then add a few measures of the excerpt back here and there – something like this:

Then maybe up the dynamic again, add some more notes – so on and so forth, until you’ve added all of the notes back in with the correct dynamic markings. These breathing exercises will show you where you may be wasting air, where you can afford to save some air, and exactly how much air you need to refill your tank at each of the breath marks.

Follow the contour of the line, and don’t expel any extra air when you don’t need to! This especially comes into play nine after Q – the flute plays solo there, so there is no need to push and crescendo, especially since rising in register is often naturally accompanied by a slightly louder dynamic.

Two last tips for Mendelssohn’s Scherzo:

- Remember that the first note is a pickup. Isolate just the D to the G, ensuring each note can clearly speak. Finding exactly where to aim to get both to speak can be tricky! To be honest, I often slightly slap on the D so it comes out clearly – a good trick as long as the sound of the slap doesn’t interrupt the music.

- This excerpt features a trifecta! A trifecta is a phrase in which each item is bigger than the previous, like the saying “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness!” In music, it appears as something repeated three times, with the third leading into another idea. The trifecta in the Scherzo starts one before Q – notice how Mendelssohn marks a crescendo going into the third iteration of the idea, and it then starts to diminuendo into a descending motive. As you move through this musical trifecta, make each statement bigger than the last – but be careful to maintain a consistent tempo!

Do you have any other tips or tricks when it comes to working on the Scherzo to A Midsummer Night’s Dream? How did these strategies work for you? I’d love to hear from you in the comments!